(Second half of interview of Joseph Papin [JP] by Leonard Lopate [LL], Aired December 14, 1987)

LL: “We’re talking with Joe Papin who is more than just a courtroom artist—we’ve introduced you as a courtroom artist—but you have illustrated Washington and UN scenes; military and international affairs; medical, financial, sports and industrial events. Your work has appeared in Harper’s, in Newsweek, in Business Week, in The Reporter, in American Heritage, in Forbes, even in Playboy, the National Review, to present the other side; you contribute to the Herald Tribune, The New York Times, and for the past eighteen years you said, been on the staff of the Daily News. You’ve won all sorts of major awards; [illustrated] 45 adult and children’s books as well, and the winner of six Page One Awards for graphic excellence in journalism—wow, incredible career!”

LL: “But that doesn’t mean that you’re treated with any more respect than anybody else (“none whatsoever”) when you’re out there. I understand that there was a bit of a run-in with a Mafia bodyguard when you were covering the Gotti trial.”

JP: “Oh, it was magnificent really, because you see, artists establish a rapport with the people—there is no barrier. After a little while, you would far rather say hello, be civil, establish some human contact. And it’s quickly done, because as I say, everyone is concerned about how they look. There’s often recesses, at each opportunity most of the people quickly come over. You say, ‘Hello, how are you.’ They say, ‘Let me take a look.’”

JP: “And one day, at the Gotti trial, I was drawing, with my head down toward my paper, when a well-manicured hand appeared under my nose, and a deep voice said, ‘What’s this.’ And, recalling my two years in the Army, and the idea that when I asked a major one day if the order I was about to give was a proper one, he said, ‘Who cares if it’s proper. But never forget the command voice and the command posture.’ I looked up and I saw a man who had both.”

LL: “And a gun probably as well.”

JP: “No, John had nothing on.”

LL: “This is John Gotti himself?”

JP: “John Gotti himself, and I said, ‘I don’t understand.’ And he said, ‘This.’ Again, without extending a finger, his hand clasped, he threw his hand down in front of my drawing. I said, ‘I don’t understand what you’re talking about.’”

JP: “He said, ‘Look. The judge is old. You’ve drawn an old judge. Good. But this.’ And then I recognized that he was pointing to a picture, to a drawing of Diane Giacalone, the U.S. Attorney on the case. He said, ‘You’ve drawn her pretty. She isn’t pretty, she’s ugly.’ And immediately the group joined in. One said, ‘She’s skinny.’ Another one said, ‘Entombed.’ Another one said, ‘Embalmed.’”

JP: “And I thought, ‘Oh my, that’s really wonderful!’ I said, ‘Look Mr. Gotti, I’ve got to do the best by everyone I draw.’ He said, ‘The judge, good; this, ugly.’ And he turned on his heel and walked away.”

LL: “Well you made him look good-looking.”

JP: “Well he is a prepossessing man, and he does have, ah, a charisma, there’s no doubt about it.”

Joseph Papin Courtroom Illustration Collection, Library of Congress number: PR 13 CN 2015:128.1349

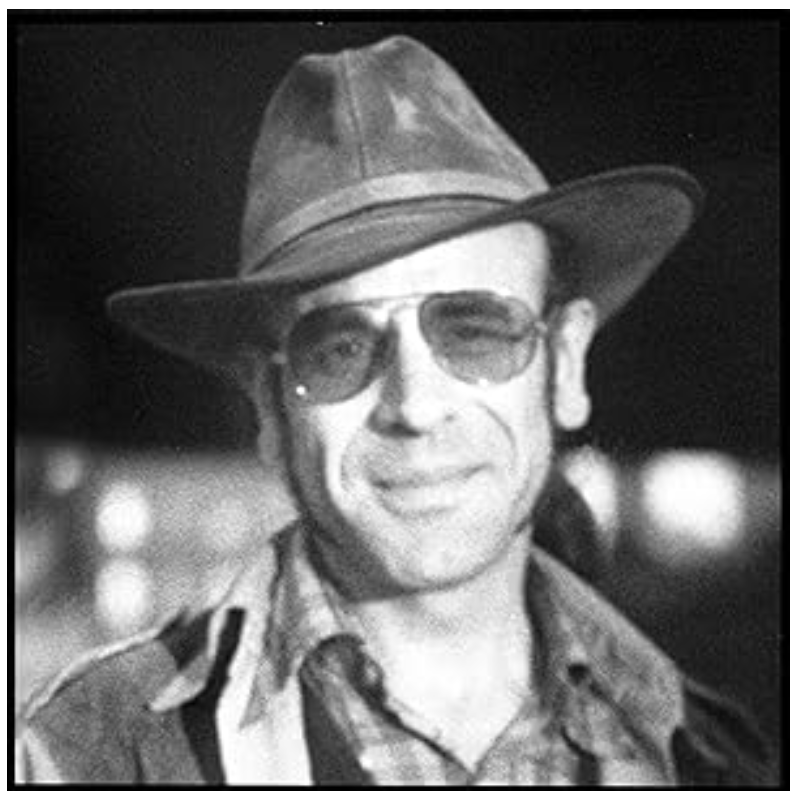

Joseph Papin, Daily News, September 5, 1986

Joseph Papin, Daily News, September 11, 1986

LL: “How conscious are you of the proceedings themselves, are you so involved in capturing the likeness and the drama of the moment that you sometimes lose track of just what’s going on?”

JP: “Well the only disability I suffer from is a loss of hearing, it started in the Army, but I try to pay as acute attention as I possibly can because I feel it’s my obligation, not only to draw, but to understand the mechanics of what is happening so that I can be as accurate and as objective as possible.”

JP: “It just so happened that following, when I wrote this, I mean when the reporter listening in on the Gotti episode said ‘Gee, this will make a great story. I said, ‘Please put in to it that everyone is concerned with how they look.’ Instead, he wrote—”

LL: “In the New York Times.”

JP: “No, the Daily News—said that, ‘Papin said that they’re all exceedingly vain.’”

JP: “Well two days later I got in the elevator and there was Rampino, the very broad-shouldered enforcer, and Carneglia, described as the bodyguard, and he said, ‘Hey, how come you don’t draw’—he said, no, ‘How tall do you think I am?’ ‘Six foot three.’ He said, ‘Why do you draw my head on the same level as the others?’ And I said, ‘Well because the editor’ and he said, ‘Never mind that, from now on draw me standing up.’ And Carneglia leaned forward and he shook his jowls at me and he said, ‘You think I ought to lose a little weight?’ and I said, ‘Not really.’ He said, ‘We’re doing a picture of you and you’re not going to like it.’ I said, ‘You are?’ and he said, ‘That’s right.’ And he said, ‘And when it’s done, we’re going to publish it in the Mafia Magazine.’ A wonderful little antidote, and really—”

LL: “In a way they have more to complain about with you than if you were a photographer, because a photographer just snaps the picture, but you have the ability to make somebody look better, look worse, you could make them smile or frown—”

JP: “Well I always say if there’s any complaints, that’s a large wart on the end of the nose with three or four hairs coming out, but in reality I don’t do that. There is—”

LL: “But do you editorialize, do you think that if you’re watching a trial and you develop a sympathy for the defendant or for somebody else on the trial that even subconsciously you draw them in a more sympathetic way?”

JP: “Well, possibly a rape victim or something of the sort, or a child who’s been abused, but the point of it is that some of these people are so prepossessing and their activities are so self- defining by their vigorous gesticulations or their shouting or screaming—at the Howard Beach trial sometimes you hear this thunder, thunder and screaming and posturing—and it reminds one of Oliver Wendell Holmes’ famous advice to young lawyers that if they had the law, to pound the law, if they had the facts, pound the facts, if they had neither the law nor facts, to the pound the lectern, and by Jingo, there it is.”

LL: “You watch the coverage of the trials on television after you’ve covered them during the day, do you get a feeling that the public really doesn’t know what’s going on? I am totally confused about what’s going on in that Howard Beach trial—I read the newspaper articles, I watch the television coverage, and yet I’m not sure who’s making the best impression there.”

JP: “Well I think, you see, the News does not share my work with television, therefore it appears only in print—if it appears. But watching what the others do [the other courtroom artists], because I understand it, I can see how beautifully they have synthesized and gathered together, in the 60 seconds or so, or maybe two minutes at the most, what they must be able to show pictorially—and visually it is always striking—it is the very heart of what’s going on.”

JP: “Now sometimes, unfortunately, the film tends to make it an event, an entertainment. And we must know, and we must be able to understand, what is going on, in order to have some sort of an opinion rather than just ‘oh they’re making noise out there, or someone’s either being railroaded, whatever.’ The lawyers get a chance to re-try their case, outside in the hallway, or on the courthouse steps, and they often do so.”

LL: “But the jury sees a long day’s proceedings, the same thing that you see. What do you think is going on in the Howard trial case?”

Joseph Papin, Daily News, November 3, 1987

JP: “Well it is a case where, unfortunately, I think the noise is all that there is to—it was a mob, there was a victim—the best face one can possibly put on it is that it was an accident—but it was an accident because of certain reasons and certain people were there, and everyone in our life is accountable. And, the lines are drawn. The jury must decide, of course, to what degree, but once the ingredients are shown—someone coming through the neighborhood, other people protesting it, for whatever reason—something terrible happened. The facts are presented—and the facts are presented—weight is given to it, and the summations are going on now. So the best they can do is try to explain the case of their particular client, hoping for some indulgence from the jury, or some special circumstance to plead the reasons why—they have to decide.”

LL: “You have watched more trials than some theater critics have seen plays and I imagine you are a real expert on them. Do you think at times, ‘Wow, this lawyer is botching up the job,’ or, ‘This guy is winning all sorts of points.’ ‘This is a great witness.’ Do you watch them as well as drama?”

JP: “Oh, without a doubt. There are some lawyers who can talk, some scream, some put it all together, and as Barry Slotnick is elegant and mannered and never raises his voice, David Breitbart, whose favorite expression is that ‘cross-examination is the blast furnace of truth’ is a magnificent cross-examiner. And he moves, from the back—you watch him feint, his shoulders—he’s a compact little guy, and he moves just like a fighter. And when he delivers his big punch, you’re ready for it. It is—some of these men are magnificent in their command of their hands, their voice, and of course, they know the facts and they know the case. I’m often rewarded just to be able to be present when some of these people are trying their cases.”

LL: “In Howard Beach, the most prominent of the defense attorneys is Steven Murphy, do you think he’s good?”

JP: “Well he’s certainly loud, and I think he’s double-jointed. He moves so many ways and so many different, I did a little funny cartoon showing him as a banty rooster in the beginning. But he does assault. He is an old-time type lawyer and he just literally grabs the jury by the nape of the neck and just screams into their faces—what he wants them to understand is his version of what happened.”

LL: “Do you get a feeling about how a trial is going to go since you’ve been to so many, do you get a feeling that this one is a not guilty verdict or a guilty verdict?”

JP: “Well yes, you do get a feeling and sometimes you’re very surprised, because with Giuliani having a blitzkrieg against the mafia, the mob, and one trial right after the other—going down like ten pins—John Gotti and his entire crew were acquitted, and it was stunning, absolutely stunning. Just before the verdict came in, he was over looking at my drawing, and as though to put a finish, and a pleasant one, to all of the talk that had gone on, he said, ‘I just want you to know that I think your drawings are wonderful and worth $5,000 each.’ I said, ‘Gosh Mr. Gotti, you should be my editor!’ He said, ‘He thinks I should be his editor.’ Just then the jury came in and he was pronounced ‘Not Guilty’ by a foreman who said everything he had to say in strong direct response to the question for the clerk on each and every count: ‘Not guilty,’ ‘Not proved,’ Not guilty.’

JP: “Some you die for, like Jean Harris. I mean a poor woman put into that situation, and, my own mother, in growing up, told me that one should never mess with a schoolmarm, and unfortunately the judge, in solemn tones, said that he was constrained by law to sentence her, there was nothing he could do. But he apologized for having his hands tied. Other cases, you’re just glad the people are convicted because they’re bad, bad people.”

Joseph Papin, Daily News, February 18, 1981

Joseph Papin, Jean Harris Breaks Down on Stand, February 6, 1981 (Library of Congress, Drawing Justice)

LL: “Have you ever been at a trial where you felt that the decision was a gross miscarriage of justice, where you saw incompetence in one of the lawyers, or a judge who came in with a bias of his own, or her own?”

JP: “The judges, according to some attorneys, are the prosecutors’ best friends. There are cases, I suppose, where I would have thought that the case could have been made better than through an informer. When an informer gets up there who has turned, like Jimmy ‘The Weasel’ Frattiano. Cardinali, in this case [Gotti trial], he admitted to killing seven people, showing remorse for only one who happened to be a college kid. He said, ’But they wanted him killed’ so he dragged him out and shot him behind the ear, when in actuality, I think he had accounted for twenty-five. I thought—”

JP: “Or up in New Haven, at the corruption trials. Giuliani, to me, could be an evangelist on the circuit, he radiates righteous and damnation for the sinners. You know that it’s a holy fire coming. On the other hand, the man who is their main witness was such a disgusting, repulsive person—he had done everything that one could possibly do outside of murder—and the old joke about the sex therapist with his patients is a joke until you run across someone who’s up there who’s actually done that. Yet time and again, his version of things, and with his marvelous recall, won the day, and you knew ultimately he would be plead for by the attorney’s office, and he got a very modest sentence. All the others, you know—Justice.”

Joseph Papin, Geoffrey Lindenhauer is cross-examined by Thomas Puccio (Daily News, October 4, 1986)

LL: “You’re an artist who comes out of a long tradition of artists who’ve covered public events. Are you conscious of the line back to Daumier and beyond?”

JP: “Oh yes, I think we all know our antecedents. And where I went to school, working my way through school at Ohio State, I like to say—‘round on the ends and high in the middle’—we learned the fundamentals. And the fundamentals were taught again and again and again so that one learned hand-eye coordination and you learned to draw exactly what was there. So by the time you were on the scene, being a reportorial artist, objectivity and honesty—being true to what you looked at—was part of the standard that you tried to adhere to.”

JP: “I remember my first job, I was still on active duty and I’d gone to see Harper’s Magazine’s Russell Lynes—he entertained one afternoon a week. He would let artists into his study, a little library, and we would sit along the wall and then he would come up, and you would put your things down in front of you and he would look at them. Ramrod straight, with iron gray hair and steel-rimmed glasses. There was this young lady ahead of me, my first time, and she put down her portfolio. He said, ‘Young woman, do you read my publication?’ and she said, ‘Yes sir, I do.’ He said, ‘I doubt that, or you wouldn’t take my time and the time of these good people with pastels, good day.’”

JP: “So I put my things down and he said, ‘You have no portfolio?’ I said, ‘No sir.’ He said, ‘You don’t even have anything in order?’ I said, “No sir.” He said, “But you did these drawings where you drew them, is that true?’ I said, “Yes sir.’ He said, “Are you in the Army?’ I said, ‘Well I’m just getting off active duty.’ He said, ‘This isn’t the Army, this is civilian life, you can forget the sir.’ He said, ‘So few artists attempt or risk anything by drawing on the scene.’ He said, ‘This is wonderful, if you come back in two weeks I’ll have a job for you.’”

JP: “So I came back in two weeks and he said, ‘Do you know Mike Burger at the New York Times?’ I said, ‘No sir, I know no one.’ He said, ‘Well I do,’ and he picked up the phone and he said, ‘Mike, I’m sending over someone who draws like a wizard, help him out on that article that you’re doing on The Gay Old Lady—the New York Times.’”

JP: “I met this magnificent person and I was so stunned when I realized what an enormously famous man he was that I didn’t ask him if ever the chance were to be I could ask him to put my drawings to his words. But the magazine published by five pages of drawings and so the old rocket began to lift off. Up to that point freelancing—I never did have an agent. I couldn’t get work from the smaller ones because I had nothing at all printed and the big ones said well you don’t have anything from the smaller ones. Consequently, I thank my wife for sticking with me all that time.”

LL: “Yeah but you’ve done very well for yourself since, you probably are the most famous newspaper artist right now in New York. One more question before you leave, Joe. Is there a special seat that you prefer in a courtroom, do you like it—you’ll take any seat that they give you?”

JP: “I’m happy to be there at all. The seat I’d prefer would be right alongside the judge (LL: “They don’t let you sit there”). But judges indulge us—some judges are so wonderful. Judge Leval, at the Pizza Connection. At the Sharon trial—Judge Sofaer let us sit in the well of the court. And of course, to this day, Judge Weinstein in Brooklyn is so kind to artists. He’s one of the few judges, by the way, who need not wear a black robe to be truly magisterial in his demeanor. So if the artist can simply be there, reflecting, in his own unique way, this moment of history, I think he adds an invaluable contribution.”

Judge Sofaer, Sharon Trial, Joseph Papin Courtroom Illustration Collection, Library of Congress number: PR 13 CN 2015:128.2006

LL: “Well Joe Papin is one man who no courtroom—no courtroom, what am I saying—no camera can ever replace and I hope that there will always be a place in our courtrooms or in the events of the day for him. I’m very, very pleased that he’s visited us here on New York and Company. Thank you so much for having visited us. Thank you.”

JP: “Thank you.”

Judge Leval, Pizza Connection Trial, Joseph Papin Courtroom Illustration Collection, Library of Congress number: PR 13 CN 2015:128.3586

Judge Weinstein, Judge Brennan Arraignment, Joseph Papin, Daily News, August 1, 1985

Leave a Reply